Chapter 7: landscapes

Mom did a few studio landscapes, probably combining photographs with her own imagination. Below is an elegant example, a cross between Venice and the Oregon Coast (9a). It has a serenity befitting “La Serenissima,” as Venice was called.

But a new energy took over her work once she was back outdoors, as she had been with her vacation sketches. A “pleine aire” (open air) art group organized by Clackamas Community College art professor Leland John took their oils and easels into nature, to paint what they saw and felt, like the impressionists of old. They even came to Mom’s farm occasionally. One of Mom's pastels (9b) shows either her or one of the other women in the group.

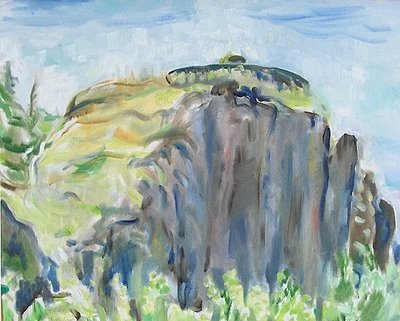

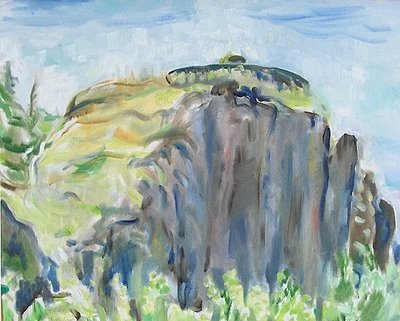

Other places the group went were the Columbia Gorge (9c) and Sauvie Island (9d, with a painter in the foreground).

For one of these group outings, we have aa photo of Mom at the scene (9e) as well as the painting in the photo (9f).

Robert Joki, of the Sovereign Collection gallery in Portland, considers this last one her best oil painting. The title, “Rock-water dance,” shows another way Mom put her dance training into her painting, besides simply painting dancers. The water dances on, with, and around the rocks, and both with the hills beyond. The hills flow down to the water, as much as the water flows over the rocks. The rocks are the least fluid, a masculine bastion of security (as I theorized in Chapter 5) for the feminine fluidity of the rest of the painting.

A companion piece is “Les danseurs des Fleurs de Soleil,” the Sunflower Dancers (9g). They stand in a field like a mother and two children, all dancing together while the trees go wild with delight in the background. Mom learned French in Lausanne, Switzerland, at age 11, where she spent a year in boarding school while her mother studied art in Paris. Even in the 1990s, Mom enjoyed conversing in Swiss-French with a Swiss woman-painter her own age she met in her classes. Moreover, I think the French way of saying the title--literally, “The Dancers of the Flowers of the Sun”--gives a grandeur and mystery to the title that the English compactness loses.

These titles suggest a way of seeing many of Mom’s outdoor pieces. Two tree trunks, for example, become two dancers, one tall, sleek and calm, the other wildly flaying its branches about (9h). The flaying limbs of the shorter one compensate for a dark, hidden, scarred center.

Other paintings suggest a similar interpretation in terms of dance. “Fall colors” is the dance of the trees with each other and with their reflections in the shimmering lake below them (9i).

Another piece (9j) offers us a magical reimagining of Multnomah Falls. The trees beckon to each other, even as they are kept gently apart by the dancing waters of the falls.

In another work (9k), the colors of a fantastic sunset glide by and through each other like ghostly dancers, anchored by the firm reality of the bushes in the foreground and the city shimmering in the distance.

In another twilight scene (9l), colors dance above the summer woods and the boats in bed for the night.

Some dancers dance solo. A solitary tree on a hillside leans toward the valley below (9m):

A magic fruit tree breaks into song in a magic garden (9n). This oil is probably a reworking of a sketch she did visiting John and Louise in Northern Virginia one spring (9o, below).

I don't think that this last tree is drawn as a singer. Back in Oregon again, however, look at this towering matriarch of a cottonwood tree, at the end of a long season, shedding its leaves as a person might her teeth. Even so, she raises her head in dignity, singing a hymn to heaven (9p).

Finally, in a sketch done at a tree farm near Estacada, it is as though a whole chorus of trees were singing joyfully in colorful harmony (9q):

Music, including the human voice, was as important to Mom as dance, as we shall see explicitly in the next chapter. When she painted the Christmas trees, she was probably also performing a lot for the Oregon City Senior Center chorus in their annual Christmas presentations at retirement centers.

In the newspaper clippings Mom saved, there is an essay she wrote on dance. It appeared in her weekly column, “Nancy’s Notions” in the early 1980’s. She says, “To me true dance is God-sent, unspoken, profound, a religious expression not to be taken profanely: the Quakers and Shakers in my dance background support me.” In that spirit, she says, she performanced a dance in church on Christmas Eve. Against those who might look askance at such behavior, she replies, “How does anyone dare to insult the profound dance of the ancients—the dance of David, the dance of the Greeks, the athletes of Sparta, the rituals of Africa, of Japan, of Spain, of Stonehenge, of Hawaii, of the Americas? The penalty for such insult is great.” In referencing dance in the titles of her paintings, she is showing us something more: Dance not only attunes us to the sacred when done in a sacred way by humans, but when we see it in nature, then we become attuned to the sacred in all of nature as well. Mom told her friend Diana Marsden, in one of their many conversations about Divine Substance, that the artist has the power to reveal the sacred all around us. Her dancing landscapes help us to see her point.

But a new energy took over her work once she was back outdoors, as she had been with her vacation sketches. A “pleine aire” (open air) art group organized by Clackamas Community College art professor Leland John took their oils and easels into nature, to paint what they saw and felt, like the impressionists of old. They even came to Mom’s farm occasionally. One of Mom's pastels (9b) shows either her or one of the other women in the group.

Other places the group went were the Columbia Gorge (9c) and Sauvie Island (9d, with a painter in the foreground).

For one of these group outings, we have aa photo of Mom at the scene (9e) as well as the painting in the photo (9f).

Robert Joki, of the Sovereign Collection gallery in Portland, considers this last one her best oil painting. The title, “Rock-water dance,” shows another way Mom put her dance training into her painting, besides simply painting dancers. The water dances on, with, and around the rocks, and both with the hills beyond. The hills flow down to the water, as much as the water flows over the rocks. The rocks are the least fluid, a masculine bastion of security (as I theorized in Chapter 5) for the feminine fluidity of the rest of the painting.

A companion piece is “Les danseurs des Fleurs de Soleil,” the Sunflower Dancers (9g). They stand in a field like a mother and two children, all dancing together while the trees go wild with delight in the background. Mom learned French in Lausanne, Switzerland, at age 11, where she spent a year in boarding school while her mother studied art in Paris. Even in the 1990s, Mom enjoyed conversing in Swiss-French with a Swiss woman-painter her own age she met in her classes. Moreover, I think the French way of saying the title--literally, “The Dancers of the Flowers of the Sun”--gives a grandeur and mystery to the title that the English compactness loses.

These titles suggest a way of seeing many of Mom’s outdoor pieces. Two tree trunks, for example, become two dancers, one tall, sleek and calm, the other wildly flaying its branches about (9h). The flaying limbs of the shorter one compensate for a dark, hidden, scarred center.

Other paintings suggest a similar interpretation in terms of dance. “Fall colors” is the dance of the trees with each other and with their reflections in the shimmering lake below them (9i).

Another piece (9j) offers us a magical reimagining of Multnomah Falls. The trees beckon to each other, even as they are kept gently apart by the dancing waters of the falls.

In another work (9k), the colors of a fantastic sunset glide by and through each other like ghostly dancers, anchored by the firm reality of the bushes in the foreground and the city shimmering in the distance.

In another twilight scene (9l), colors dance above the summer woods and the boats in bed for the night.

Some dancers dance solo. A solitary tree on a hillside leans toward the valley below (9m):

A magic fruit tree breaks into song in a magic garden (9n). This oil is probably a reworking of a sketch she did visiting John and Louise in Northern Virginia one spring (9o, below).

I don't think that this last tree is drawn as a singer. Back in Oregon again, however, look at this towering matriarch of a cottonwood tree, at the end of a long season, shedding its leaves as a person might her teeth. Even so, she raises her head in dignity, singing a hymn to heaven (9p).

Finally, in a sketch done at a tree farm near Estacada, it is as though a whole chorus of trees were singing joyfully in colorful harmony (9q):

Music, including the human voice, was as important to Mom as dance, as we shall see explicitly in the next chapter. When she painted the Christmas trees, she was probably also performing a lot for the Oregon City Senior Center chorus in their annual Christmas presentations at retirement centers.

In the newspaper clippings Mom saved, there is an essay she wrote on dance. It appeared in her weekly column, “Nancy’s Notions” in the early 1980’s. She says, “To me true dance is God-sent, unspoken, profound, a religious expression not to be taken profanely: the Quakers and Shakers in my dance background support me.” In that spirit, she says, she performanced a dance in church on Christmas Eve. Against those who might look askance at such behavior, she replies, “How does anyone dare to insult the profound dance of the ancients—the dance of David, the dance of the Greeks, the athletes of Sparta, the rituals of Africa, of Japan, of Spain, of Stonehenge, of Hawaii, of the Americas? The penalty for such insult is great.” In referencing dance in the titles of her paintings, she is showing us something more: Dance not only attunes us to the sacred when done in a sacred way by humans, but when we see it in nature, then we become attuned to the sacred in all of nature as well. Mom told her friend Diana Marsden, in one of their many conversations about Divine Substance, that the artist has the power to reveal the sacred all around us. Her dancing landscapes help us to see her point.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home